April 2015 was a month of success for the MIHARI network. Five community-managed Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) in the network finally got their permanent protection status, after years of waiting. These new MPAs cover areas of high importance for marine biodiversity as well as for traditional fishing communities including Velondriake and Soariake in the southwest of Madagascar, Ankarea and Ankivonjy in northwest and Ambodivahibe in the North.

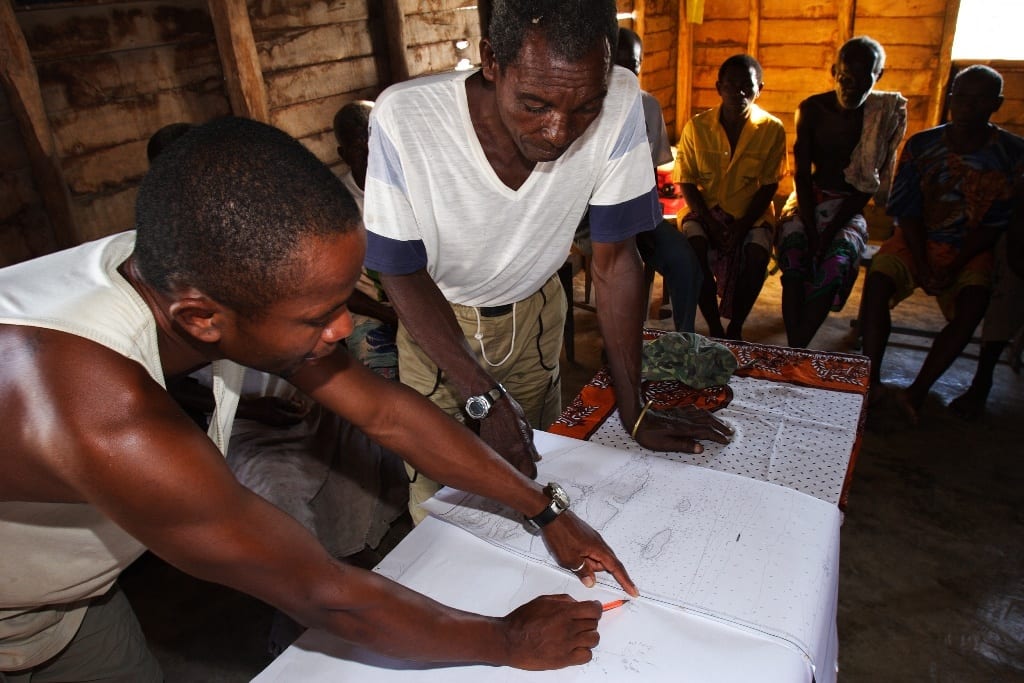

These MPAs result from a decade-long process towards integrating local communities into the management of natural resources as part of the expansion of the protected areas system of Madagascar. Furthermore, they have contributed greatly to the realisation of the 2003 Durban Vision, which envisaged an increase in the area covered by protected areas for Madagascar from 1.7 million hectares to 6 million hectares.

Unlike “traditional” MPAs, locally managed marine protected areas are created both by, and for, the local communities that depend so heavily on the natural resources that these areas generate for their subsistence. These MPAs aim to ensure a good balance between traditional uses of resources and the protection of biodiversity, and are classified as category 5 or 6 of the IUCN (International Union for the Conservation of Nature). Obtaining permanent protected status not only creates a sense of ownership in coastal communities, but also serves as an important way to secure community rights, in that it can harmonise economic development activities in the area while at the same time limiting the activities of the industrial fishing fleet.

In this article, we take you on a tour to discover these five exceptional sites in Madagascar sharing their stories and the journey they followed to become a community-managed MPA…

Velondriake: the first locally managed marine area in Madagascar

Velondriake means “to live with the sea”. The LMMA was established in 2006 and obtained temporary protected area status in 2010. Community activities started with the management of important economic resources, such as octopus, but MPA status was sought as a way of securing the rights of local fishers to their resources. After several years of waiting and hard work on the part of the community and Blue Ventures, the NGO that supports them, the MPA finally got its status of permanent protection (Decree 2015-752) on April 28, 2015. In addition to community pride in managing an MPA, one of the benefits of obtaining the status of permanent protection is to increase the power of the management committee to implement the management plan and decide on the MPA’s direction.

In the words of Roger Samba, the president of the Association Velondriake: “Now that we are officially recognised as an MPA, we’ve noticed a sharp decline in infractions and a better use of resources. We suddenly feel stronger and have more power to handle all the paperwork issues outside Velondriake […]. One of the things I really appreciate is the fact that now external agencies are formally obliged to consult with local communities and seek official authorisation from the Velondriake committee before working in the area.” He also noted however that there was a significant workload attached to managing the protected area which has to be taken into account.

Soariake: the cradle of one of the largest reef systems in the world

The new MPA, with an area of 38,293 hectares, is, like its neighbour Velondriake, located on the largest reef of Toliara in the southwest of Madagascar. The Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) has been working there since 2008 to support the Soariake Association, the organisation that represents the interests of 7,000 people living within the MPA. It is recognised that Soariake has a second barrier reef which has exceptional potential for regenerating coral species. The special feature of the new MPA is that that its communities live solely from fishing, yet they were highly motivated to create the MPA. At the same time, seaweed and sea cucumber farming activities are being developed. Soariake is also very advanced in terms of community surveillance involving the CCS (Control and Supervision Committee).

Ankarea and Ankivonjy: sister MPAs sheltering exceptional biodiversity and with a high potential for tourism

Ankarea (Decree 721 in 2015, set up only in 2011) and Ankivonjy (Decree 722 in 2015, set up in 2010) are neighbouring MPAs in the region of DIANA in the northwest of Madagascar. With a total area of 275,096 ha, they are some of the few remaining refuges in the Western Indian Ocean for dugongs, whale sharks, sawfish and Madagascar fish eagles, all of which are endangered species. In 2012, these two MPAs were identified as potential UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Their local communities are acknowledged as being very dynamic and motivated in conservation.

The Ankarea MPA contains an important seabird colony within its strict conservation zone known as called “the islet of the four brothers”. The Ankivonjy MPA, contains an island called Nosy Iranja which is considered the foremost nesting site for green turtles and hawksbill turtles in Madagascar.

Ambodivahibe: redefining the concept of “protected area” in the perception of local communities

Ambodivahibe, with an area of 39,764 ha, is located in the northeast of Madagascar and is an important protected area in terms of marine biodiversity. It is composed of four villages in the municipalities Mahavonona and Ramena with a total population of 1,845, who are mostly engaged in fishing. The Ambodivahibe MPA also has an area identified within it as being highly resistant to the impacts of climate change due to its significant depth. It received its full protected area status on April 28, 2015 (Decree 753 in 2015).

At the beginning of their collaboration with the communities from Ambodivahibe, the NGO Conservation International met some difficulties and reluctance from the resident communities, who viewed the concept of a protected area with suspicion. However, by focusing primarily on community priorities, particularly the management of fisheries, the situation has taken a positive turn. The result is the implementation of the Ambodivahibe MPA in 2009 as a way of securing local user rights.

According to Luciano Andriamaro of Conservation International: “After an exchange visit to Andavadoaka, a member of one of the communities the most opposed to the idea of conservation was convinced of the need to protect marine resources. It was at this time that we changed our approach in supporting the implementation of community management measures and the establishment of marine reserves in parallel with the protected area implementation process.”

—–

Protected area status is just the first step…

In preparing this article, each agency we spoke with shared the same issue with us: full legal protection is a great achievement, but it is useless if the management on the ground doesn’t work. To avoid the risk of having a “Paper Park” where conservation does not exist in reality on the ground, there is still a lot of work to do. Managers and communities still need a lot of support from the State, and from technical and financial partners to strengthen their capabilities.

In supporting three MPAs towards obtaining definitive protection at the same time, WCS had a heavy workload over the last year to get to this point. However, Lala Ranaivomanana, WCS’ marine programme coordinator was clear that plenty of hard work was still to come, explaining: “Sustained support is essential for a long time, so that a sense of ownership can be realised in an MPA, and community structures reach a certain maturity.”

Scaling up marine management in Madagascar

The management of marine protection has an important place in the country’s national agenda following the commitments made by the President of the Republic at the World Congress of the parks 2014, consisting of tripling the coverage of marine protection in Madagascar. In marine conservation as in terrestrial conservation, agencies and decision makers are convinced that the involvement of local communities remains essential in scaling up conservation in Madagascar. However, as the stories of these five MPAs show, the work and resources involved in establishing a functional formal MPA is considerable. According to Ny Aina Andrianarivelo of Blue Ventures: “We have seen that obtaining permanent protection status for an MPA is long and complicated, slowed by the availability of state agencies and by cumbersome administrative procedures. Furthermore, the costs of environmental impact studies and topographic zoning can be exorbitant. This is well beyond the reach of local communities unless they have considerable support from a technical and financial partner.”

While some sites such as the Barrens Islands are still working towards full protection within the protected areas system, the MIHARI network includes many more communities involved in local management of resources that will be an asset in achieving the Promise of Sydney, but for whom formal MPA status remains out of reach.

Ny Aina of Blue Ventures continued: “To achieve the promise of Sydney and ensure both food security for coastal communities and the protection of marine biodiversity, we need a more favourable legal system to facilitate local management and guarantee the rights of traditional fishing communities.”